Do you seem to get injured easily when you increase the amount of running you do? Are you keen to work towards a half-marathon or marathon but get stuck at 10km? Have you spent hundreds or thousands of dollars on the perfect running shoes to find that you still have pain?

It can be easy to decide that your body doesn’t want you to run further than 5 or 10km if you have hit a wall with your training in the past. It can also be frustrating to be held back by your aching body when you really want to run more.

Running can be an excellent form of exercise, but it is important to understand how your body responds to running (and other exercise) to make sure you can run further without pain.

Research shows us that the single biggest factor contributing to running injuries isn’t the wrong shoes, it’s not an incorrect cadence, it’s not the wrong foot placement, it’s training error.

Training Errors

Training error is thought to be responsible for up to 80% of all running-related injuries. This means that most of these injuries are preventable if you are willing to make some changes to the way you plan and progress your runs.

Common examples of training error include:

- A sudden increase in running volume, intensity or frequency

- An inappropriate mix of high and low intensity workouts

- Inadequate rest and recovery between runs

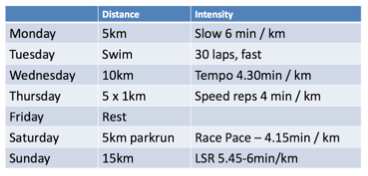

The most important tool in determining training error is to take a good look at your weekly running schedule. Like the example below, this should include:

- Overall volume (total km per week – 40km in the example below)

- Intensity of each workout

- Running Surface (hills / track / road / flat / trails)

- Other exercise in the week (eg. strength sessions, swimming, cycling, flexibility work)

Putting Theory into Practice

Once you have established your weekly schedule, and tracked it over a few weeks, it can then be much easier to identify why injuries might be occurring. Some simple steps to minimise injury can be:

- Don’t progress your overall volume too quickly – establish an initial weekly running volume that doesn’t cause pain, and only increase your total volume by 10% each week.

- Recognise the importance of rest and recovery – your body and tissues need time to adapt to training, so make sure you factor rest days into your week. Also plan for a recovery week in your training program after three weeks of consistent 10% increases.

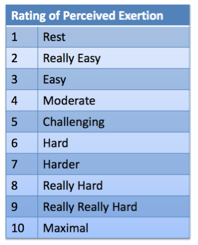

- Do most of your training at low intensity – you should try to have an 80:20 split between low and high intensity runs – use a Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale to determine where your training zones are. Long Slow Runs should be at up to 4.3 on the scale (80% of all training volume), Tempo Runs at 4.3-6.5 (12% of training volume), Speed Work at over 6.5 (8% of training volume)

The key method to prevent running injury as you increase your load is to plan your training well, and increase load gradually.

If you have been struggling with running and need a professional opinion to determine if there are any other factors leading to potential injury, please contact any of our clinics for a thorough initial assessment.

Happy running!

References

- Seiler S. What is best practice for training intensity and duration distribution in endurance athletes? Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2010 Sep;5(3):276-91. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.5.3.276. PMID: 20861519.

- RO Neilsen et al Excessive Progression in Weekly Running Distance and Risk of Running-Related Injuries: An Association Which Varies According to Type of Injury J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2014;44(10):739–747. Epub 25 August 2014. doi:10.2519/jospt.2014.5164